Regional Cultures: Ukrainians

Ukrainian culture is right at home in our community, from delicious cuisine to lively dance. Canadian Ukrainian culture is special—it follows old traditions long left behind by most modern Ukrainians, creating an oasis of folk customs.

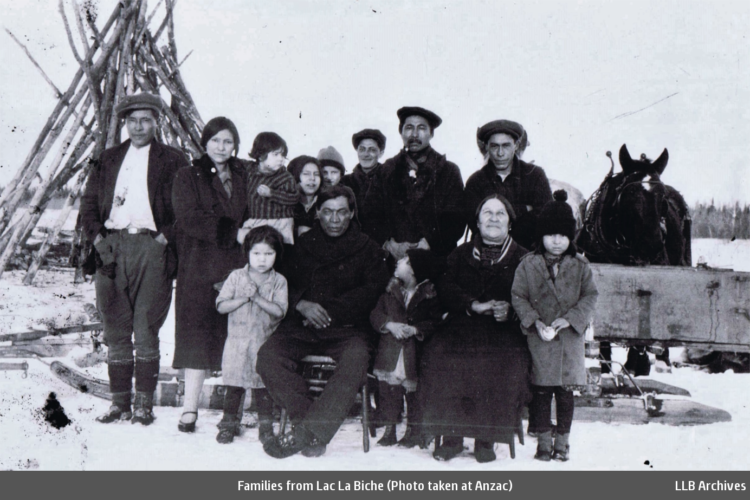

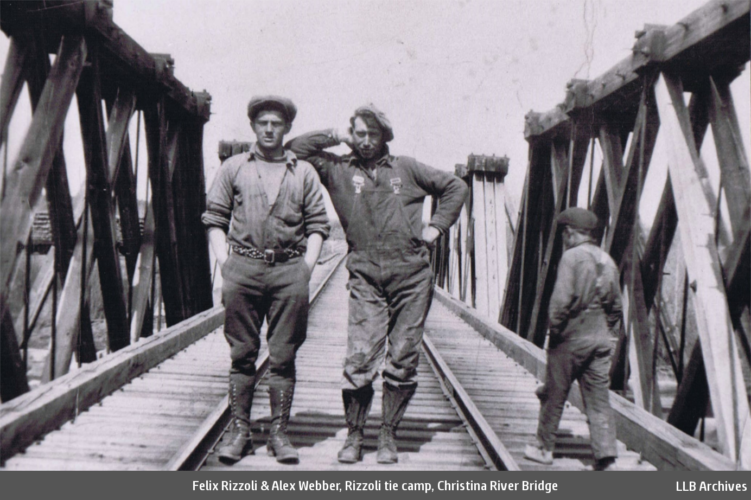

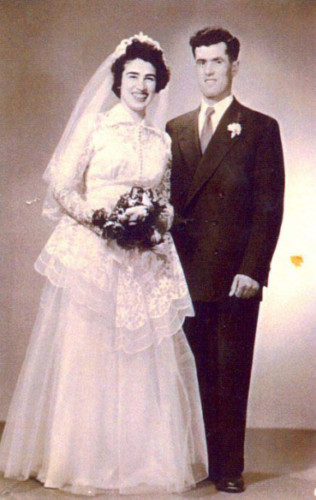

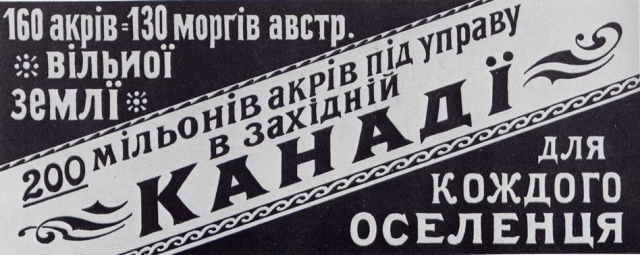

The first wave of Ukrainian settlement in our region occurred in the Venice and Craigend areas between 1929 and 1932. During the early 1900s, the Canadian government’s immigration policy favoured farming experience over country of origin. This brought thousands of Ukrainian farming families to western Canada. The majority of Ukrainians who arrived in Canada came from western Ukraine under many names—Ukrainians, Ruthenians, Galicians, and Bukovynians. These Ukrainians were among many new Canadian farmers who put many hours of hard labour into clearing land to make it suitable for farming.

Many families learned Ukrainian at home as their first language, reading and writing in Ukrainian before learning English in school. In the early 1980s, the Ukrainian Cultural Society of Lac La Biche offered Ukrainian language classes as well.

“My grandfather was army personnel in Ukraine and he kinda figured there would be another war coming up. They said they had to get out of there. So him and his wife packed up six kids and got on the ship and came to Edmonton in 1930. They wandered around to get a homestead out here in Lac la Biche. They went to Wandering River; they [had previously] went to Peace River country and it was too far away from the markets and all that. Wandering River was still too far. They liked the train. There was a creek there and they settled right down in 1935. It took them 5 years to get a place for themselves. They were just like nomads walking around. Y’know, the challenges they had in those days… they were in a strange country, they didn’t know the English language. They came with a trunk of clothes packed with six kids.”

—Eugene Uganecz

Members of both the Ukrainian Orthodox and Ukrainian Catholic religions often follow the Julian calendar for their religious holidays. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church is a Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic Church, while Roman Catholics belong to the Latin Church and follow the Gregorian calendar. The Julian calendar, named for Julius Caesar, is about two weeks out of alignment with our current calendar, the Gregorian calendar, which is named for Pope Gregory XIII. This means, for example, that Christmas is celebrated in January. While the Catholic church in Ukraine follows the Julian calendar, churches in Canada sometimes have permission to follow the Gregorian calendar instead.

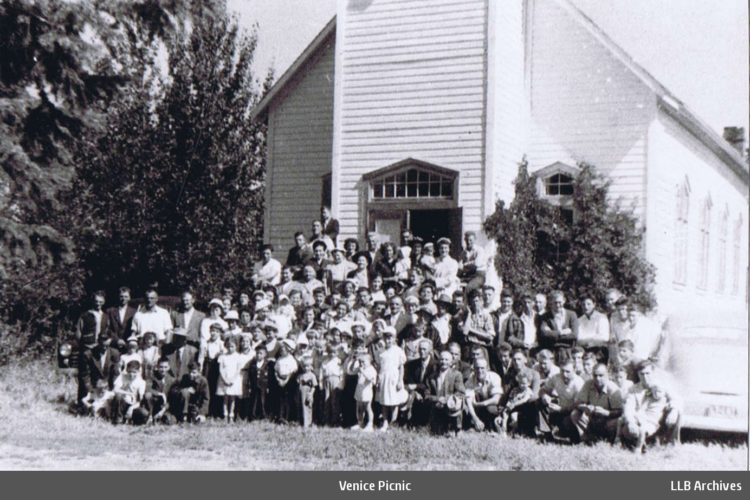

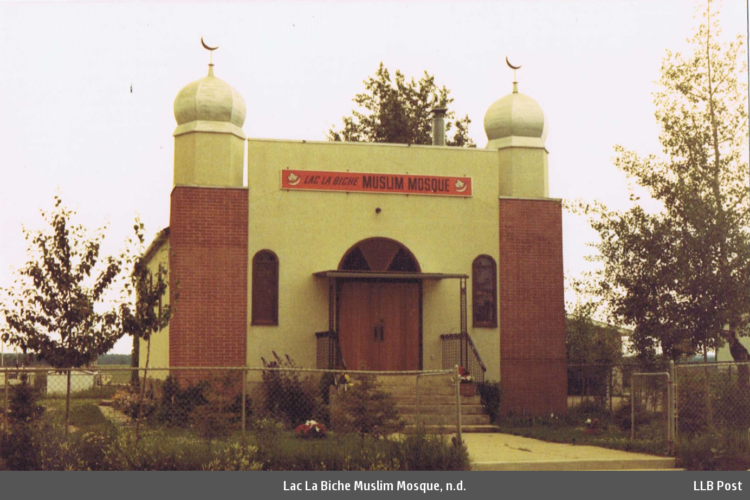

In 1931, the community of Craigend began planning for the first Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church in the region; however, services were eventually moved to Lac La Biche. In 1955, construction began on a new church, the All Saints Orthodox Church, which was built through volunteer labour and community effort.

One of the most important Ukrainian holidays is Easter. Joyous exchanges of “Khrystos voskres!” (“Christ has risen,” Христос воскрес) and “Voistynu voskres!” (“He has risen, indeed,” воістину воскрес) can be heard in churches as families bring a basket of paska (паска, round Easter bread), babka (бабка, cylindrical Easter bread), boiled eggs, meat, cheese, and pysanky (писанки, dyed Easter eggs) to be blessed by the priest. Pysanky (singular: pysanka, писанка) are decorated using dyes and beeswax. Wax is placed on an egg by a kistka (кістка), a tool with a small funnel attached where melted wax is inserted. The wax protects the colour underneath from the dye in which the egg is placed. There are several symbols used on pysanky, including (but not limited to) geometric designs, Christian images, plants, animals, and man-made tools. Dye colours also have special meanings, such as blue for good health and yellow for the harvest. In regards to Easter, this year (2017) is quite special—Easter falls on the same day on both the Julian and Gregorian calendars.

“On Easter we bake bread: paska and babka. We put them in baskets and take them to church. Everybody brings their baskets and puts them in a semi-circle where a priest comes and blesses everything. What else do we do at Easter? We have a little sip of holy water. He blesses the holy water and he brings some home.”

—Loveth & John Beniuk

Malanka (Маланка), the New Year’s celebration, is named after Malanka, the daughter of Mother Earth, whose return marks the beginning of spring. During Malanka, one can eat many delicious treats, such as kutia (кутя), a dish of poppy seeds, wheat, honey, and almonds, symbolizing peace, prosperity, and good health. Ukrainian staples such as varenyky (вареники, often called perogies or pyrohy by Canadian Ukrainians), grechka (гречка, buckwheat) pancakes, and kielbasa (колбаса, sausage, often called kubasa by Canadian Ukrainians).

Ukrainian dance is characterized by rhythmic stamps, acrobatic jumps, and elegant twirls. The national dance, Hopak (гопак, from the verb гоп, “to jump”), is the most popular dance with impressive solos. Concerts often begin with the Pryvit (привіт, “welcome”), a welcome dance complete with the traditional offering of bread and salt. Various costumes are worn for the Pryvit, showcasing the regional dances performed during the concert. Most other styles of Ukrainian dance are named for the regions they come from, such as Polissia, Volhynia, and Bukovyna (Polissian, Volyn, and Bukovynian respectively). The Lac La Biche Cerna Dancers performed these traditional dances on stage for many years.

Ukrainian embroidery is easily recognized. Traditional embroidery patterns vary according to region of origin and are often characterized by kalyna (калина, guelder-roses), poppies, lozenges (diamonds), and geometric patterns. Red and black are standard colours used for embroidery, but are often accompanied by blue, yellow, and green. Embroidery is put on the regions where evil spirits could enter the body to protect the person wearing it—at the cuffs, neckline, back, shoulders, and hem.